The BC Provincial Court’s Northern Region is serviced by 17 judges working in 31 communities spread over an area the size of Alberta. Judge Dennis Morgan describes the challenges and rewards of judging in that vast region.

“One obvious challenge is the travel. Many of B.C.’s northern judges will drive well over 20,000 km each year. There are also ‘fly in’ circuits that bring their own challenges, including reliance on informal weather reports to the tune of “Yes, I can see the mountains, sort of.”

For northern BC judges, white knuckle winter driving, and the ever-present risk of colliding with large animals becomes commonplace. (ICBC reports an average of 2600 animal crashes in north/central BC each year, resulting in 140 injuries and 3 deaths.)

Photo courtesy of Andy Abenthung

Judges travelling the northern circuits have had some unique experiences: such as Judge Steven Point’s return flight from Haida Gwaii, when, tragically, a prisoner suddenly opened the door of the small plane, struggled free from a sheriff, and jumped to his death; or when Judge Elizabeth Bayliff was driving to a remote circuit court location, came across a crashed all-terrain vehicle, and drove the injured driver to the local nursing station before continuing to court.

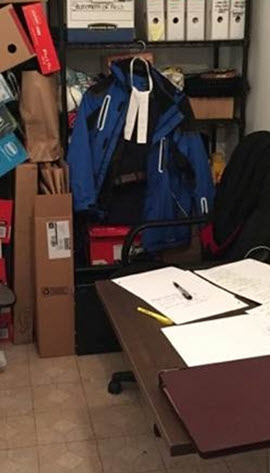

Another challenge in bringing court to small remote communities is arranging appropriate facilities. Anahim Lake is fortunate to have a dedicated ATCO type trailer complete with a hitching post built by an offender doing community work service. In Kwadacha, the gymnasium attached to the Band office works well as a courtroom, and one may be comforted by a friendly local dog nosing around the folding table that serves as the judge’s bench.

Photo courtesy of Andy Abenthung

Judges working in small communities can expect a lack of anonymity that brings obvious challenges, but, less obviously, also brings possibilities for higher personal rewards. Within my first few weeks of sitting in the single judge town of Quesnel, I asked a man if I could drive on his vacant lot to access my backyard. He granted permission and casually mentioned we had met before. He rolled up his pant leg and displayed his electronic bracelet.

On another occasion, I was giving a talk in the courtroom to students from a local alternate school, when one pre-teen girl mentioned, without any hint of ill-will, that I had put her dad in jail. I told her lots of people will make a mistake in life but that does not mean they are not good people. She seemed to sit a little taller, and I realized how important it was to her to have her peers hear this.

Judges in small communities have the benefit of immediate community input. As a result, they may be better able to distinguish between an offender’s behaviour, often rooted in addiction, and the person. Learning how a person is viewed by, or involved in, the community helps greatly in crafting appropriate sentences with the ultimate goal of public safety, best obtained, as it is, through offender rehabilitation.

In small communities there is a more obvious continuity between history and the present. A lake in one area is named after a local Chief’s family. A lawyer descends from an early settler and a bridge is named after her family. The relevance to judging is that very often system participants are from long time, well respected local families, and the reputation of local justice hinges as much on the judge’s conduct during trial as on the ultimate decision.

Photo courtesy of Andy Abenthung

Understanding historical influences helps not only, for example, to ratchet down a long festering ranchers’ dispute, but is also crucial to improving judicial relationships with First Nations communities.

In the Cariboo/Chilcotin many First Nations witnesses seem reluctant to attend court. Their distrust may stem from events now referred to as the “Chilcotin War”. In 1864 a government decision to build a road to Cariboo gold fields through traditional territory, the rape of Tsilhqot’in girls and a threat to intentionally inflict smallpox, stirred a group of Tsilhqot’in to wage what has been referred to as a guerilla style small scale war against the road builders and settlers. Six Tsilhqot’in Chiefs were induced to turn themselves in on a promise of immunity and a belief they would negotiate peace. Instead, they were arrested, tried, and hung as murderers. The majority of the hangings took place in Quesnel. Before he died, Chief Klatsassin said, “We meant war, not murder.”

On October 26, 2014 - the 150th anniversary of the hangings - representatives from government and the Tsilhqot’in nation participated in a redress ceremony at the location of the hangings. I attended and observed the strong emotions that those 150 year old events still evoked, and was affirmed in my belief that to fully understand local concerns small town judges should know the local history.

In summary, notwithstanding the challenges, judging in the small and often remote communities of beautiful northern BC is an absolute pleasure and privilege.”

A version of this article first appeared in the 2015 Summer edition of the

Provincial Judges Journal.